The Project

The Hypothesis; Site-Climate is Critical

In 1989, Hilda and Earl began thinking seriously about trying to resolve the mystery of America’s missing Tempranillo, and as scientists, they knew good research was the key to success. To prepare for the project they began by reading anything on viticulture and enology, especially anything that pertained to Spain and Tempranillo. Wine critics and authors mostly agreed that wine quality in Rioja came from its soils.

It soon became obvious they had to identify the precise quality factor that drives production of fine Tempranillo wine in its native land. Earl headed to Spain and quizzed Rioja bodega owners, winemakers, and wine merchants; they confirmed that Rioja’s unique soils and skilled winemakers explained its 150-years of fame as the world center of fine Tempranillo production.

But Earl was bothered by the fact Tempranillo grapes grown in the three fundamental Rioja soil types, even when made at different bodegas by different winemakers, tended to produce relatively similar, excellent wines. Many commented that wines from higher elevation vineyards, like in Rioja Alta, produced notably better wine than grapes sourced from Rioja Baja, leading to the idea that elevation was a quality factor. Then, Earl's scientific mind found a clue pointing to a different quality factor.

Some 150 miles to the southwest of Rioja lay the valley of the Duero River where Bodegas Vega Sicilia had produced fine Tempranillo wine for over a century. Critics said Vega, the only famous producer in the region was a special exception to the supremacy of Rioja. Then in the early 1980s Alejandro Fernández, an upstart producer located 10 miles from Vega Sicilia, began making the highly regarded Tempranillo wines mentioned above that had inspired Earl.

But why could the Duero region which had very different vineyard soils and vineyard elevations a thousand feet higher than those in Rioja also produce fine Tempranillo? Therein might be a clue to Tempranillo’s real quality factor. Earl dug through volumes of Spanish agriculture records comparing Rioja, Ribera del Duero and other Spanish regions. The data revealed that Rioja and Ribera’s growing seasons were of similar length and the daily temperatures of the growing season were also similar. The Ribera had greater diurnal temperature swings and slightly colder winters. Both regions had similar rainfall patterns especially in the growing season. Earl also took note that Spanish provinces like Valencia and La Mancha that produced Tempranillo wines of lower quality also had longer and warmer growing seasons.

Back home on the Gulf Coast, Earl and Hilda poured over their findings and began to think climate might be the quality factor. Next, their son Greg Jones, a hydrology major at the University of Virginia assisted in obtaining detailed weather data from several Spanish wine growing regions that created mounds of 11” x 17” perforated sheets of paper. Pulling the clues together, they concluded the elusive Tempranillo quality factor was climate: specifically, a relatively short growing season with a cool spring and hot, moderately dry summer cut short by a cool autumn. Their new theory also explained the disappointing history of California Tempranillo and the lower quality Spanish Tempranilllo produced in regions that had a longer and warmer growing season. The climate theory even explained the quality difference between Tempranillos from Rioja Alta and Rioja Baja.

Greg obtained his bachelor’s degree in 1993 and enrolled as a PhD candidate in atmospheric science at Virginia. This change of focus would lead to a new understanding of the impact of climate on viticulture around the world, and of course at Abacela. In addition, while conducting his PhD research in France he noticed that bud burst, the springtime awaking of grape vines, was occurring earlier. This finding was among the first biological based data that documented the warming of Bordeaux’s climate. He received his doctoral degree from Virginia in 1997.

The Hypothesis is;

To produce fine, age worthy wine from the Tempranillo grape it is critical that the vines be grown in a location where the climate provides a relatively short growing season characterized by a cool spring, a hot moderately dry summer cut short by a cool, truncated autumn.

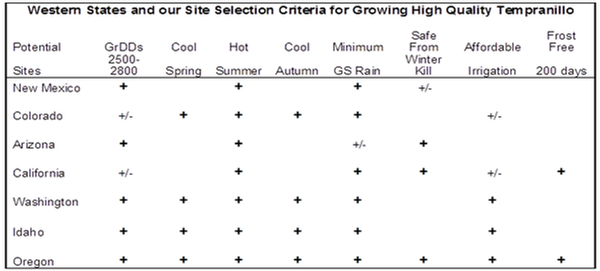

What was needed now was to locate a Spanish Tempranillo homoclime somewhere in America and test the hypothesis. They studied maps of the climates of the 48 states and quickly eliminated whole swathes of the USA in which the growing season was too cool, too hot, too long or excessively rainy. The search narrowed to seven Western states: New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, California, Washington, Idaho and Oregon. Greg obtained airport climate records for these areas for detailed analysis ; yes, more of those 11 x 17 perforated sheets. With calculator and spreadsheet in hand the data of California’s long growing season and historical record of not producing Tempranilllo as a varietal wine confirmed it was not the best choice. New Mexico was appealing but its combination of really short growing season and late spring frosts was worrisome; a visit with some vineyards there confirmed these risks were real.

With airport weather records, Earl put his legs to work scouting Idaho, Washington and Oregon as the most likely states to find an ideal Spanish Tempranillo homoclime (see table below).

The Joneses visited the Boise Idaho and Washington growing regions and found them attractive but eliminated both from consideration because of the risk of deep winter freezes (below 10 F for extended periods) that might kill untested Tempranillo vines. Springtime frost were also problematic. Parts of Oregon especially some locations in the western valleys met all their hypothesized criteria. The eastern Oregon was like Washington, the north (Willamette Valley) was too cool and wet for Tempranillo but Oregon’s south west valley’s held promise of near-perfect homoclimes to Rioja and Ribera.

“At that point it appeared all we had to do was identify an optimal location for a vineyard site in Southern Oregon.” ~Earl