Earl Jones: Bringing Tempranillo to America

Earl Jones: Bringing Tempranillo to America

By Lance Cutler, Wine Business Monthly (PDF)

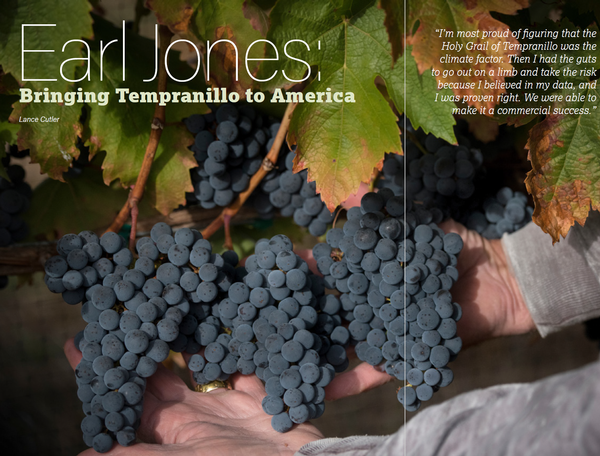

“I’m most proud of figuring that the Holy Grail of Tempranillo was the climate factor. Then I had the guts to go out on a limb and take the risk because I believed in my data, and I was proven right. We were able to make it a commercial success.”

EARL JONES GREW UP on a Kentucky farm, driving a tractor between rows of corn, wheat and soybeans. He attended Tulane University where science, especially medical science, became his passion. He earned a medical degree in dermatology but pursued a career as an immunology researcher, preferring that to working directly with patients. He was teaching at Emory University in Atlanta when he met his future wife, Hilda. Their pursuit of a Tempranillo Holy Grail would establish that grape as a major variety in the United States and in so doing helped change the direction of Oregon viticulture and winemaking.

Earl Jones was first introduced to Tempranillo wines in San Francisco at Lucca’s Deli on Chestnut St. He lived in the area in the mid-1960s, and Mike Bosco, the owner, would recommend inexpensive Rioja wines. So inexperienced was Jones that he first thought Rioja was the name of the grape, but he liked the wine, and it was cheaper than California Cabernet, which at the time sold for just $2 to $3 per bottle.

“My family didn’t have wine on the table,” he explained. “Going to the big city and being involved with other researchers, I often found myself at the dining table with people used to drinking wine. I liked the taste of wine. I’d never been much on hard liquor or beer, but wine struck me very differently.”

As his research career took off, Jones went to Europe often. Thanks to Mike Bosco at Lucca’s, he’d enjoyed Rioja wines and thought they went well with the meat and things he liked off the grill. He had also come to love the Spanish culture during his multiple trips to Spain. When he got older, higher salaries enabled him to drink up the hierarchal tree of Tempranillo. The more he drank, the more intrigued he became.

Having lived in California, Jones knew that California had never developed Tempranillo into fine wine. In fact, by 1963 Amerine and Winkler from UC Davis discontinued research on Tempranillo. “What the hell?” thought Jones. “California can grow almost every other grape. What’s wrong with Tempranillo? That really turned on the researcher in me.”

Every time he went to Europe, he’d be sure to make his way to Spain to find out what they did that was different. He quickly learned he couldn’t find out anything about where they grow the fruit by going to large wineries because they weren’t talking. So, he started going to small wineries, concentrating on those right on the edge of where they could grow good Tempranillo. He was stunned to learn that these wineries didn’t have weather stations. He couldn’t find out anything about their climate. He did find out about their soils—they had three or four different types, but the wines coming off those soils weren’t that different from one another.

In the extreme eastern part of Rioja, which used to be called Rioja Baja but is now called Rioja Oriental, the elevation is lower, and the climate influenced by the Ebro River is different. Spaniards don’t like the Tempranillo that grows there. They prefer the higher elevations, which are cooler with a shorter growing season. Spanish winemakers told Jones that it was the elevation at which the grapes were grown that was the key. That, and having a great winemaker.

Touring the small wineries had led Jones to one great winemaker, Alejandro Fernández, who founded Tinta Pesquera in Ribero del Duero in the 1970s. Fernández showed him that you didn’t have to grow Tempranillo in Rioja to make excellent wine. That fascinated Jones because all the books and written papers agreed that Rioja was the place to make Tempranillo primarily because of the elevation there. The success at Tinta Pesquera suggested that wasn’t true.

Jones went down to talk to Fernández. The winemaker agreed that elevation was the key quality component. That made no sense to Jones: “Elevation can’t be the key because Ribera del Duero, where Alejandro Fernández has been making great wine for years, is 1,000 feet higher and has different soils.”

THE REAL DETERMINANT OF OUTSTANDING TEMPRANILLO

Jones kept digging. Finally, he got some agricultural aides and equivalents, along with some climate and rainfall data. The remarkable thing was that Ribera del Duero and Logroño in Rioja had almost identical growing season climates. The dormant season was a bit colder with more rain in Rioja, but otherwise, the climates were remarkably similar. He had a lead.

Jones studied the data and learned that Tempranillo in Spain thrived in a climate that had about a six-month growing season with a cool spring, a dry summer, extremely hot days and really cool nights because of the diurnal swing. All the Tempranillo fruit in the Rioja Alta and the Ribera ripened in October, just as the heat of summer was disappearing and the days were getting shorter. Then he looked at the winters and discovered they were moderate. They were cold but not frigid. He decided that must be the essential growing season for high-quality Tempranillo. Jones had stumbled onto something important. He theorized it wasn’t the elevations or the soils that made great Tempranillo wines: it was the climate.

“Once I understood the fastidiousness of Tempranillo’s requirements for that climate, then I could see why California screwed it up. I thought, ‘That’s like a mountain unclimbed. I think I may exit medicine and try to find a place in the United States that could grow good Tempranillo.’ But I didn’t know if such a place existed.”

Javier Tardaguila, the professor of precision viticulture at the University of Rioja, has known Jones for 15 years. “I agree with Earl that climate is a key factor for Tempranillo wines, but soil also plays a key role, not only in controlling vigor and yield, but also in contributing a moderate water stress in Tempranillo vines. Tempranillo is a high-yield variety, so poor fertility and shallow soils in Rioja and Ribera, in combination with the cool, dry climate, make the best Tempranillo wines in Spain. Earl has become a worldwide expert, and he’s passionate about Spanish grapevine varieties. His search has led him to the best terroir for Tempranillo, Garnacha and Albariño in the United States.”

FINDING A HOME FOR THE GRAPE IN THE U.S.

In looking for a site to plant his vineyard, Jones set up four criteria. He wanted to minimize frost risk by planting on hillsides, preferably located above wide valleys. He wanted sunny south-facing hillsides with minimal foggy or overcast days to maximize heat summation. To minimize vine vigor, he hoped for rocky, well-drained hillside soils, and given the low midsummer rainfall in the areas he was searching, he needed a site with access to irrigation water.

Jones needed information and specific data. In a happy coincidence, Jones’ son, Greg, was studying to be an environmental scientist, focusing on hydrology and water resources. Working towards his Ph.D., Greg Jones had access to libraries, stacks of data, good record keeping and loads of climate information. As Greg researched for Earl, he found there were no climate scientists studying viticulture and wine production. Just as importantly, while the viticulture and wine worlds knew about climate, their knowledge was nowhere as complete as that of climate scientists. The younger Jones saw a niche. While helping his father, he decided to redirect his studies to climate and viticulture.

Greg put it this way: “There were some interesting timing issues. What he was doing really helped me and what I was doing, I think, really helped him. All I did was provide him with some data to help him make decisions but what he did for me was to open my eyes to what I could study for my Ph.D. program. His pursuit helped me hone my interest in terms of studying climate and viticulture.” Currently [Previously] the Director of the Center for Wine Education and a professor of Environmental Studies at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, Greg Jones has become one of the world’s foremost experts on climate change as it affects viticulture.

Earl Jones’ quest started in New Mexico because his daughter was living in Albuquerque, and he thought New Mexico kind of looked like Spain. It turned out that the growing season was not good there. Frost late in spring and frost early in the fall were common. That motivated Jones to study other western climates. He was still travelling a lot to give talks on his research, so he visited several Western states. He’d rent a car and drive out somewhere to get weather data from the local airports. It was an interesting time. Jones found the best climate fit to be in Idaho, Washington and Oregon, but deep winter freezes that occurred in Washington and Idaho concerned him. He worried those cold temperatures could kill Tempranillo vines.

Once he got to Oregon, Jones kept moving west until he arrived in southern Oregon. He started looking in the Medford area but discovered that the Umpqua Valley had a more moderate winter, so he went up there. By this time Jones was fairly committed to leaving medicine and embracing this dream project, provided he could find a property and afford it. He believed the data, so he renewed and intensified his search in the Roseburg area.

Jones checked the data at the Roseburg airport and started looking for a site. Armed with 7.5-minute topo maps, he had driven around a bit but found he couldn’t see over the hills well enough. Returning to the airport, he hired a local bush pilot to fly him around the area. He told the pilot he wanted to fly over the places that had the least fog and were the sunniest in the spring and fall. The pilot said the best areas were south of Roseburg. They took off, and he marked the roads on the maps with a yellow highlighter. Jones went back to the airport, got his car and drove around to look for the topography he wanted.

“There were some vines here already,” Jones explained, “but they had made some terrible mistakes, planting in the river bottoms and things like that. I wanted to be in a classical situation with down sloping hills with a shoulder that sat up above the valley floor. I found a place that was perfect. This guy had 3,500 acres and wanted to sell 460 of them. The spotted owl crisis was dropping real estate prices, and his asking price was very reasonable, so I let him talk me into it.”

In 1992 Earl and Hilda Jones became land-owners in Oregon. They named the property Abacela, which means “they plant a vine.” After identifying the right climate and buying the land, Jones looked up the latitude and found he was just 30 miles farther north than Rioja. That struck him as a wonderful coincidence because being at the same latitude gave him virtually the same solar angle. That meant the sunlight exposure on his vines was going to be about the same as it was in Rioja. He thought, in addition to climate, that was really important.

His property wasn’t a perfect match to Rioja, but it was close. The Spanish elevations were quite high while the elevation at Abacela was between 500 and 800 feet. It rained a bit more at Abacela in the winter, but in the growing season Rioja and the Ribera had more rain than Roseburg. He was able to locate his vineyard with access to irrigation water so he could adjust for that. He had this property that seemed as close to Rioja’s climate as possible. It had the same solar angle, and it had access to water. He decided to go for it.

“We started liquidating everything. We sold our house, quit our jobs, packed up our two daughters and moved into a rented house. We got to Oregon on July 29, 1994. We owned 463 acres, but there was nothing on the land, not even a road. When my father came for a visit, he told me, ‘Son, you’ve lost your damn mind.’”

Hilda looked at it differently. “Moving across the country didn’t bother me. I come from an immigrant family, and my husband is very thorough with his research. It wasn’t like he just came home one day and said, ‘Let’s move.’ I completely trusted his thorough process and what he had seen.”

Moving ahead with his project meant Jones had to get some Tempranillo vines. UC Davis had Tempranillo cuttings, but they were obligated to give them to California growers first. Once California growers declined the cuttings, Jones swooped in and took all the cuttings he wanted. He also got Tempranillo budwood from Porter Lombard at the Southern Oregon Regional Experimental Center. He took the cuttings to three different nurseries, not wanting to put all his eggs in one basket. He received the grapevines that winter and planted them, as dormant vines, in the spring of 1995. He was 54 years old.

A COMMUNITY FILLED WITH SUPPORTERS

University people don’t make a lot of money. Starting his business quickly took all the money he had. Jones did something he had never done before, taking a part-time job with a local dermatologist to help keep shoes on the children’s feet. He worked there for several years.

Hilda was along with this project from the start. His data had her convinced. She helped in the vineyard, did a lot of the planting and drove a tractor. She was emotionally and physically invested in this project just as Jones was. Earl and Hilda also had two kids still at home, one four and one 12. Jones figured if this didn’t work out, they’d sell the land and go back to the university, but it worked out, and their kids were able to grow up in the business and participate as well. Hilda and Earl have five kids between them, and all of them have been involved in the Abacela business one way or another.

With that first planting, they put in 13 different varieties, including 4 acres of Tempranillo. The varieties they were confident would work, like Malbec and Syrah, got planted in 1.5-acre plots. Th ey planted two or three rows (just enough to make a barrel of wine) of the more esoteric Spanish varieties, like Grenache, Mazuelo and Graciano, along with some other varieties that might not work. Th at got them off to a start. Jones had no winemaking experience, but he had a lot of experience with laboratory organisms, and he had worked with pathogenic organisms, so he figured he could probably make wine.

What Hilda and Earl were doing was a big change from what had been going on in Oregon up to that point. When they got there, Burgundians were growing the fi ve international varieties: Pinot, Riesling, Merlot, Chardonnay and Cabernet. At the time, farmers were growing them all in the same valley and the same vineyards, sometimes even in adjacent rows. They had little regard for when what ripened or how it fit into the growing season.

Tempranillo, because of its finicky nature for a particular climate, made Jones very aware of matching variety to climate. He never planted anything that didn’t fit the climate. He established some rules: if the vines budded out and (in his estimation) produced perfect fruit between the frost-free periods, and if it ripened and tasted a lot like that same variety grown in Europe, then he was going to bottle it.

They bottled their first Tempranillo in 1997. It received favorable recognition. Jones needed to build a business, so he took his Tempranillo to local restaurants. In Roseburg, they didn’t know what the hell it was. When he took the wine to Portland, he got a quite different reception. “I remember going into a great little high-end Spanish/Mexican restaurant called Blue Azul. I poured a taste for the wine buyer, and she asked me where I got the grapes. I told her I grew them. Then she asked who made the wine, and I said that I did. She tasted again and said, ‘This is the real thing.’ She bought two cases.” Jones would have similar experiences wherever he took it after that.

He had put their phone number on the back label, which turned out to be the smartest marketing thing he ever did. People would go into these restaurants, have a bottle of wine and take down the phone number. Since they only had one phone, that number on the bottle connected to their house. Typically, they’d get calls on Saturday or Sunday morning about 9 a.m. Callers would inquire if it was Abacela Winery and then ask to buy a case of Tempranillo. Sometimes they couldn’t even pronounce it.

“At first, we didn’t know what to do. Then we realized we could ship the wine. We’d take their address, have them send us a check and I’d mail the wine. Then they started asking to come down and visit the winery. At that time, our winery looked like an equipment shed. We got a couple of sawhorses and put a piece of plywood on top of that and covered it with a white sheet. That became our tasting room right there in the equipment shed.”

SUCCESS SPURS EXPANSION

The next 1998 vintage was the one that rung the bell. Jones entered it into the San Francisco International Wine Competition, and it took a double-gold, first-place award, besting all the Spanish entries. Since he had virtually no winemaking experience, he was convinced the grapes had made the wine delicious. They had been grown in the right climate. The break-through was strictly related to climate and had nothing to do with soil or great winemaking. He felt proud and vindicated.

The only building they had was the equipment shed, so they converted part of that into the winery and part into the tasting room. Jones would plant small increases of vines as he could afford it from the cash flow. He wished he could have planted all 76 acres at one time, but he couldn’t afford that. Jones didn’t take out a loan until 2010, and he used that money to build a new tasting room. By then it seemed this winery thing was going to work, so he was willing to go to a bank for some money.

“It’s been such a great adventure,” summed up Hilda. “My hat is off to Earl for how well he thought things out, the vision that he had. He has laser vision, not like me. I’m always distracted. The way he can think through things is just amazing.”

Jones continued planting incrementally until their last Tempranillo planting in 2012. Since then, he has been working to remodel the vineyard. He made some mistakes with the original plantings. They have hills with north slopes and south slopes, and he had planted some things in the wrong places. He had certain clones that weren’t particularly good, so he removed the Tempranillo clones he didn’t like and replaced them with better Tempranillo material. He’s done the same thing for Malbec and Grenache. With five different soils in the vineyard, each requires its own specific irrigation and fertility management. That’s what he’s been spending money on since 2012.

As the vineyard took shape and vintages started piling up, Jones turned his focus to winemaking. He set up five principles to guide his winemaking. First, he would only pick ripe fruit that would make expressive, varietally correct, terroir-driven wine. He would process the grapes in small batches with a gravity-flow system and minimal handling to preserve fruit integrity. He’d work to gently extract skin-bound components that contribute aroma, flavor, color, texture and mouthfeel to the wine. He would moderate his use of new oak barrels to avoid overwhelming the wine’s natural flavor and aroma. Finally, he would filter only when necessary to preserve, not remove, the grape’s intrinsic characteristics.

The business was succeeding and growing, but there was so much to do. Jones and his wife needed some help. In 2003 Andrew Wenzl, a graduate of Eastern Oregon University with a B.S. degree in biology and chemistry, took a job at Abacela as cellar master. His science background fit in perfectly with Jones’ research proclivities. Two years later, Wenzl was promoted to assistant winemaker, and three years after that he officially became Abacela’s winemaker. “The concept of a gravity-flow winery was already set up when I got here,” Wenzl said. “The reasoning behind it was to help control Tempranillo’s tendency for being very tannic by doing as much whole berry fermentation as possible. We are also able to make wine without a must pump. By not pumping anything, we are not shearing or breaking open berries, and we are not exposing seeds to the must.”

Accolades became a steady occurrence. In 2001 Decanter magazine declared Abacela to be “Oregon’s most interesting property.” Abacela’s 2005 Tempranillo Reserva won America’s first Gold Medal in Spain’s 2009 Tempranillo al Mundo Competition. Jones was named Oregon’s Vintner of the Year in 2009. Abacela was named 2013 Oregon Winery of the Year by Wine Press Northwest. In 2015 Earl and Hilda received the Lifetime Achievement Award, the Oregon wine industry’s highest honor. Amidst all the awards, they’ve continued to grow slowly and steadily until now they produce between 12,000 and 13,000 cases a year.

Jones observed, “I’m most proud of figuring that the Holy Grail of Tempranillo was the climate factor. Then I had the guts to go out on a limb and take the risk because I believed in my data, and I was proven right. By sticking to the formula, we were able to make it a commercial success. I was dancing with the lady I brought to the dance by matching my data to a proper site.”

His wife Hilda added, “Did we do everything right the first time? Oh God, no. Have we done things expensively because we didn’t know what we were doing? Oh, yeah, but I don’t think I would have changed anything. I’m proud of what we’ve done. I’m proud of his vision. He was correct. We’ve been a great team, and we’ve just gotten ’er done.”

Earl explained, “As a physician, I was happy in the laboratory, working with my colleagues on theories and testing them to see if we could make some advance that would help people. But you also treat patients. Other than the interactions with those people, dealing with patients who have a disease that you can’t alter the course of can be a depressing occupation.

“Winemaking is not that way. The wine business is a happy business. I think I help a lot of people. People will taste our Tempranillo and say, ‘Wow! This is delicious. It has something to it that Cabernet doesn’t have, that Syrah doesn’t have. Nothing else tastes like this. Thank you so much.’ That makes me feel good. That’s what I mean when I say it’s a happy profession.”

Before Abacela, most large vineyards in Oregon specialized in Pinot Noir. The vineyards in the southern part of Oregon primarily grew fruit to sell to other people. Those selling fruit had to be very selective with which varieties they planted to ensure their buyers would purchase the fruit. By matching a particular variety, Tempranillo, to a specific site, Jones trailblazed a new direction for Oregon. As Abacela Tempranillo became successful in the marketplace, other winegrowers wanted cuttings. Tempranillo is now sold in more than 100 Oregon tasting rooms. The Jones’ willingness to take the risk on lesser known varieties, and their subsequent success with those varieties, changed the landscape of Oregon viticulture. “We stuck our neck out on a limb and made the decision to try these other grapes and market them as varietal wines,” Earl said with pride.

Wenzl pointed out, “Earl is a pioneering grape grower. We planted a lot of varieties for the first time in Oregon. The Abacela vineyard has always been like a huge science experiment. The ones that appear to thrive we keep; the others we abandon. It is all climate- and site-driven. We can set crop yields, the ripeness level at pick and we are careful with oak so the wine can speak for itself. When we have successes and it tastes good in the bottle, we look at our collected data and try to emulate that in future vintages.”

The Oregon Vineyard Census is published every year. It has expanded the number of varieties that it considers to be planted widely enough to enumerate in the census. Abacela is credited with introducing almost all the warm climate varieties. Abacela is thought to be the first Oregon winery to grow, produce and bottle 100 percent single varieties from the following grapes:

• Cabernet Franc 1996

• Tempranillo 1997

• Malbec 1997

• Port-style Duoro grape-based wine 1999

• Albariño 2001

• Tannat 2008

• Tinta Amarela 2010

• Touriga Nacional 2012

• Graciano 2013

Greg Jones tells a story about a day at Abacela before any vines were planted. Greg asked, “Dad, what happens if you just make okay wine? Are you gonna be good with that?”

Earl’s response was, “That is not my intent. I have no plans to make just okay wine.”

This writer has tremendous respect for most wine growers, but every now and then someone changes the way grapes are grown and the way wine is made. Earl and Hilda Jones did just that. They literally bet the farm on a dream and a theory. It took courage, guts and a lot of hard work, but they have succeeded in what they set out to do.

Lance Cutler, WBM